How A Future Supermodel Was Held Hostage By Communist Czechoslovakia

The struggle between Pavlína Pořízková’s family and communism.

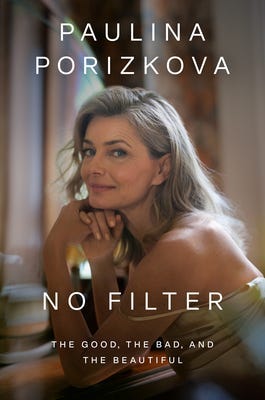

If you grew up in the 1980s and 1990s you probably know who Pavlína Pořízková is. Even if you didn’t, you most certainly have seen her photo somewhere. “An American supermodel of Czechoslovakian descent,” is what you would find with a quick Google search. In fact, she was the first supermodel from Central/Eastern Europe to obtain such worldwide success, and it was virtually impossible not to run into a photo of her in fashion or beauty magazines -and their covers- back in the day. During a recent interview for PBS, Pořízková briefly recalled her impressions of Czechoslovak communist totalitarianism: “We were taught this from preschool and on, that we would be praised for delivering the news to, you know…Help the country to weed out those terrible people, who were, you know…Making us suffer by spreading lies.’ […] The real terror of occupation, of being occupied…Is not having to stand in a bread line at three o’clock in the morning, and the fact that you only really have flour and lard to eat and that you will never get new clothes, or there’s only one Barbie in a toy store in the entire city. Those are not the dangers…Those, you can navigate around. The danger is that you cannot rely on your belief. Your brain is occupied…It’s like an alien takes over your brain and starts making other decisions for you”.

Not many people, however, know the dramatic story of Pavlína’s family’s escape from Czechoslovakia. And I believe it’s a very interesting one.

Jiří Pořízka, “enemy of the people”

Pavlína’s father, Jiří Pořízka, was anti-communist from birth. His family had aristocratic origins, and he was educated in the Catholic faith, which was strengthened in his childhood years by his convinced and enthusiastic membership in a local scout group. In 1962, when he was only 22 years old, Jiří was arrested for distributing a few leaflets with religious content. “Enemy religious ideology” in the language of the regime. The sentence: two and a half years imprisonment, reduced on appeal to a year and a half, and the label of “enemy of the people” that would cost him a demotion from office clerk to manual worker in the textile company where he had always worked in Prostějov, Moravia. He would be rehabilitated in 1968 thanks to Dubček’s reforms and the Prague Spring, which would also mean a return to the office he had to leave because of his “crime”.

“Enemies of the people” were systematically discriminated against by the regime in every aspect of daily life. In the case of Jiří Pořízka and his family, the state had always denied their request to obtain a passport. This had prevented Jiří and his wife Anna from chasing one of their youthful dreams: to travel abroad, to “see what life was like beyond the Iron Curtain”. The reforms of 1968, however, swept this limitation away. Pořízka decided to test the sincerity of the new Dubček course, and when filling in the passport request form, he ironically wrote this motivation: “I wish to travel to every country in the world except the Soviet Union.” The application was approved: Jiří and Anna obtained their passports. Their dream is allowed. The reforms are real.

Invasion and escape

On the night between the 20th and the 21st of August 1968, however, the dream ends: the armies of the Warsaw Pact invade Czechoslovakia. Pavlína had just turned three; Jiří and Anna feared the regime’s return to its previous form and understood they could not live with it. They quickly decided to run, and four days after the invasion they fleed to Austria on a motorcycle, taking only 2,000 Czechoslovakian crowns with them. That money would only help them to purchase a Green Card to insure their motorbike.

The decision to leave Pavlína with her maternal grandparents proved ill-fated: as the couple put down roots in Sweden, they asked the Czechoslovak government to let the little girl leave the country as well. The regime’s response is bitter and insulting: if Jiří and Anna wanted to be reunited with their 4-year-old daughter, they could do so by returning to Czechoslovakia. Where they would face imprisonment because, in the meantime, they had been convicted in absentia of illegally leaving the country.

The attempts to reunite

The only way they had to keep in touch with Pavlína was by telephone: it was comforting, but at the same time painful, for Jiří and Anna to hear their daughter sing to them on the phone. The couple decided not to give up their effort to reunite with the little girl. Appeals were made to Czechoslovak President Svoboda, the International Red Cross, and the UN International Commission on Human Rights. All in vain. That is when the Pořízka family decided to start a petition (that would get about eighty thousand signatures) and a hunger strike in downtown Stockholm. They printed about 10 thousand fliers that say “Pavlína, how much longer will you have to sing to us on the phone?”

Jiří and Anna managed to obtain the support of some Swedish MPs, and more importantly the financial help of Emil Rior, an entrepreneur of Finnish descent. But time went by, and nothing changed: the Czechoslovak government remained firm in arguing that the repatriation of the parents was the only way for them to see Pavlína again.

Suddenly, Anna Pořízková had a nervous breakdown, and that is when she and Jiří decided to accept the proposal of two young pilots, who offered to fly to Czechoslovakia and take little Pavlína back with them. Jiří gave the two young men (Christer Larsson and Karl-Goran Wickenberg) a detailed map of the town of Prostějov and a letter to his in-laws, explaining the situation.

The “official” motivation for the two pilots’ visit to Czechoslovakia was their intention to purchase a small aircraft built by a Moravian company. Larsson and Wickenberg landed in Brno on the 8th of October 1971. All seemed to go well until the moment they met with Pavlína’s grandparents. The language barrier proved decisive; Jiří and Anna’s message did not help. The two young Swedes are shown the door and given an answer to the message they had brought, where the grandparents accused Jiří and Anna of being irresponsible. Larsson and Wickenberg’s mission had failed.

It took only a few weeks, before they all decided to make another attempt, this time with a more sophisticated approach: Anna Pořízková, who in the meantime got pregnant, would claim to be Wickenberg’s wife, traveling with him on a fake id. The resemblance between the two women was striking. On the 24th of October, the small plane landed again in Brno, but Anna and the two pilots would never reach Pavlína: the police arrested them on the way to Prostějov.

At this point, the StB, the regime’s secret police, decided to raise the stakes and launch an operation aimed at breaking up Jiří and Anna’s family union. They set Pavlína’s mother free, obtained her a presidential pardon, and made sure she got financial support from the local authorities. Larsson and Wickenberg, in the meantime, are sentenced to six years in prison. They would eventually be deported back to Sweden after 12 months, where they would have no further contact with Jiří.

Olof Palme, Sweden’s PM at the time, also took action to help Jiří reunite with his family. The people in need to be saved, at this point, were three: Pavlína, Anna, and the newborn Jáchym. That is when Jiří decided to make another, ruthless attempt to bring his loved ones to safety. He got in touch with a mysterious Swiss agency specialized in “kidnappings” using special vehicles with compartments “impossible for anyone to find.” Jiří spent all the money he had left to finance this attempt. It’s the third fiasco: on the 8th of February 1973, the “compartments impossible for anyone to find” are immediately found by Czechoslovak customs agents at the Rozvadov station.

Liberation: the Helsinki Conference

Diplomatic relations between Sweden and Czechoslovakia reached an all-time low, resulting in the cancellation of two ice hockey games between the two national teams in November 1973. In the same year, in July, the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe had begun in Helsinki. Both the Czechoslovak and the Swedish Foreign Affairs ministers participate, and eventually, they got to talking about the elephant in the room. Czechoslovakia, under pressure for its hypocrisy in participating in the international conference while not granting basic human rights within its borders, finally accepts to let Anna Pořízková and her two children leave the country for good. It is the 12th of March 1974, Pavlína is almost nine years old and has not seen her father for six. But finally, the whole family is free on this side of the Iron Curtain.

Pavlína Pořízková would then grow up to become a successful model, her fame reaching every corner of the world. This could never have happened if she had remained locked up in the country-wide communist prison of the Czechoslovak regime. But the price the family had to pay for this turned out to be quite high: the operation the secret police had launched to break the union of Pavlína’s family ended up being a success. The three years spent away from her husband were too long for Anna: once they were back together, they would never be able to find love again and eventually, they would divorce. A small, bitter victory for a regime that had made a habit of destroying relationships since its inception.

At the same time, though, the whole story represents a huge PR fiasco and a bitter defeat for a system based on lies and deception. A system that, fifteen years later, would finally collapse under the longing for freedom of the very people it thought it could keep under its thumb forever.

I hope you found this story interesting! If you like my work, you can consider supporting me directly by buying me a beer here.